Look into your TV screen. You’re watching the 2025 Emmy Awards preshow coverage, and absolutely nothing looks familiar—unless you remember a pivotal moment from the 2013 version of the TV industry’s awards spectacle.

Victory Kinsky and Mia Hyndrix, 2025’s most talked-about women on Popsugar, stride up the red carpet with practiced nonchalance. They’re at the show representing Amazon Prime’s hugely popular Harlot series. Martin Henry, meanwhile, can’t conceal his joy at being nominated for Best Male Lead in the YouTube reality show Meat House. Verizon execs are also at the ceremony, lined up in tuxes to see if Charlotte Wisk will win an Emmy for her hit one-hour comedy special “Two-Headed Dog.”

And Netflix content chief Ted Sarandos watches quietly, knowingly, from the sidelines. He’s been here before, and his company leads the nomination count again in 2025 with 31 nods of recognition.

Meanwhile, viewers with long memories ask each other, “How did we get here in so short a time?”

What could possibly happen between now and the year 2025 to transform “over-the-top” video services like Netflix and Amazon into some of the most powerful players in TV land—and conversely, to recast today’s biggest networks as supporting actors?

After receiving 14 Emmy nominations this September, Netflix shows took home only one major award—a somewhat disappointing showing after “Netflix is taking over the Emmys” had echoed through the trade press in the weeks before the 2013 awards. But Netflix’s one win is hugely important because it marks the first time ever that a show that may never appear on a television network captured a major-category Emmy award.

Indeed, one day we may all look back at the 2013 Emmys as the night online TV hit a tipping point. Netflix’s nomination success is a powerful sign of an industry in transition, retooling itself to produce and distribute content that is streamed, not broadcast. As Netflix’s Sarandos told an industry trade group this summer, “We’re leading the next great wave of change in the medium of TV.”

Internet TV is following cable’s path to stardom

Internet TV is evolving faster and growing faster than cable did in its heyday. And much of that growth is spurred by critical acclaim and audience support for streaming-only original shows like Orange is the New Black and House of Cards.

By the time the Emmys began accepting nominations for cable shows in 1988, about 40 million households were already subscribing to cable service. But no cable show won a major-category Emmy until 1999, when HBO’s The Sopranoswon the award for Best Drama Series. By then, roughly 50 million households had cable (although that number has since retreated to around 42 million).

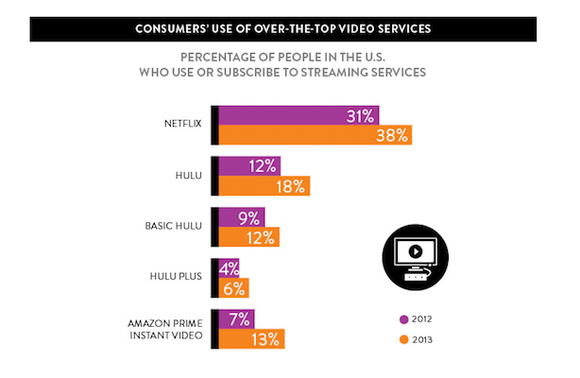

Now let’s look at Internet TV. When streaming TV shows became eligible for Emmy nomination in 2008, Netflix had only about 3 million customers for its streaming service, and Amazon and Hulu had a relative handful each. But from that starting point, it took an online video company—Netflix—just five years to win a major category Emmy (House of Cards director David Fincher won a “best direction” award this September). At the end of the first half of 2013, roughly 55 percent of the U.S. population (age 13 and up) had some type of streaming video subscription, says research house NPD. Of that total, 30 million subscribe to Netflix, at least 7 million watch the Amazon Instant Video service, and Hulu counts more than 4 million Hulu Plus subscribers.

Traditionally, streaming video services have focused mostly on volume, offering as much high-profile Hollywood content as possible. But they’re now entering a new phase where the focus is shifting toward providing original content. “The phase where everything they did was to reach a critical mass of subscribers is over,” says Albert Lai, CTO of online video platform company Brightcove. “With the switch to original programming, that’s when we see them starting to shake things up in the industry.”

Netflix has been operating as if it were a Hollywood network for some time now, but it has only recently begun speaking out about it. In its “Long Term View” statement to investors, Netflix refers to itself as a “movie and TV series network.”

The company is behaving like a network, too. Many people in the Hollywood establishment were shocked when Netflix bought two seasons of House of Cardsfor $100 million—and for good reason. “Netflix overbid for House of Cards. That in and of itself may not be sustainable,” says IDC digital entertainment analyst Greg Ireland.

But Netflix’s content chief Ted Sarandos has been very public about his desire to make a grand entrance as a new kind of content buyer, and he proved it by paying the asking price for Oscar-level acting, producing, and directing talent.

Whether Netflix’s investment in House of Cards will pay off in real dollars is anyone’s guess, but the company reported that it had picked up 3 million new streaming subscribers during the quarter when House of Cards debuted. If all of those additions were spurred by the new show, Netflix very quickly recouped almost a quarter of its creative investment.

Perhaps more importantly, House of Cards and the latest Netflix exclusive, Orange is the New Black, have made it into water-cooler chitchat everywhere. “Just like people used to talk about cable-produced shows like The Wire and Entourage at work, they are now talking about shows like House of Cards, produced by Netflix,” says Brightcove’s Lai.

At any rate, 14 Emmy nods and one major-category win give Netflix a sheen of credibility, and will certainly encourage Netflix and other streaming-only content providers to offer more original shows in the future. Netflix has already announced it plans to double its volume of original content it will stream next year.

Amazon has a good shot at a place in the water-cooler small talk as it debuts its nerd comedy series Betas, and its Capitol Hill comedy Alpha House (written by Garry Trudeau of Doonesbury fame). Amazon will also release three children’s shows: Annebots, Creative Galaxy, and Tumbleaf.

Not to be left out, Hulu and Lionsgate are now working with Brad Pitt’s Plan B Productions to make Deadbeat, a “supernatural comedy” series.

How the TV sausage gets made

As streaming-only players like Netflix and Amazon enter the content space, the traditional production pipelines for TV shows are becoming less relevant. In the past, television writers, producers, and network suits followed the same rules and worked in concert. But now long-exclusive relationships are suddenly up for grabs.

”With the emergence of online content, it’s become the Wild West again,” says Craig Anton, a comedian/actor who has appeared in Showtime’s Weeds and AMC’s Mad Men. “Everyone is taking meetings with everyone,” is a phrase you hear over and over when talking to people within the industry today. But Anton says one thing remains constant: The way to sell shows—whether to ABC or to Netflix—is by pitching them with hot, battle-proven writers and producers, or with an A-list star (like Kevin Spacey in House of Cards) attached. “The more firepower you can bring to the networks, the better the chance of success,” Anton says.

This “packaging” technique, Anton explains, became the norm back in the 1980s, when Hollywood talent agencies began serving as a one-stop shop for their friends at the networks. Because these agencies managed not just actors but also writers and producers, they could carefully assemble just the right mix of talent to a show concept and then pitch it to a network as a fully baked idea.

These days a production company, rather than a talent shop, is often responsible for assembling such packages. So if a writer and her agent can’t sell a concept directly to a network, they may go directly to a production company like Sony TriStar. If the people at the production company like the idea (and have relationships with other talent who would be good for the project), they may put money behind it, and try to sell it to a network.

Or in the more modern version of the story, they’ll pitch it to a Netflix, Amazon, or YouTube.

Nerds in Hollywood

Netflix’s Emmy recognition notwithstanding, the streaming media services still face challenges on their way to becoming visible, viable players in the Hollywood content pipeline. Anton considers it likely that Netflix has been holding meetings with various agents, managers, and production companies around town to make its intentions known, and to appear on the radar of writers, producers, and actors. Judging by the shows and talent Netflix has already been able to attract, it must be doing something right.

Netflix became interested in the women’s prison comedy/drama Orange is the New Black mainly because the series showrunner, Jenji Kohan, had a very hot name in Hollywood as the writer/producer of the hit series Weeds, which ran for eight seasons on Showtime. Kohan, who says she loved Piper Kermit’s novelOrange is the New Black, called Lionsgate contacts immediately after finishing the book, and asked them to “get it for her.” They did, and Kohan began adapting the book for TV.

When Kohan was done writing, she went shopping for a buyer. “I took it to HBO and Showtime and Netflix,” Kohan told Terry Gross of NPR during a Fresh Air interview. “And the greatest thing about going to Netflix was that I pitched it in the room, and they ordered 13 episodes without a pilot. That’s miraculous. That is everyshowrunner’s dream, to just ‘go to series’ and have that faith put in your work. They paid full freight. They were new; they were streamlined; they were lovely; they were enthusiastic about it.”

And then there’s House of Cards, produced by an independent studio called Media Rights Capital (Elysium, Babel), which had bought the rights to the source material for the show—a 1990 BBC miniseries set in Parliament—on the advice of an intern who worked there. The studio then pulled in director David Fincher and writer Beau Willimon to work on creating a new series.

Though it originally expected to sell the show to a cable network, Media Rights Capital put out feelers to Netflix’s Sarandos to see if he was interested in a licensing deal. Indeed he was, and the Netflix boss made a move that surprised everyone. The production house thought Netflix might be interested in streamingHouse of Cards episodes after they had run on cable TV, but Sarandos offered $100 million for exclusive rights to 26 episodes.

Given the company’s reputation for deep pockets and a hands-off approach toward content creation, a meeting with Netflix has become a highly desirable get in Hollywood.

Why we’re witnessing the beginning of the end

Have the streaming content companies proved anything other than that they can outbid traditional networks for hot shows? Is there something about Internet TV that both consumers and the Hollywood establishment prefer over the scheduled TV we’re used to getting from broadcast and cable networks? The numbers seems to suggest so.

“Over-the-top video is not small anymore,” says Brightcove’s Lai. “Netflix has 100 million subscribers, 30 million of those are [U.S.] streaming customers. Apple has sold 13 million Apple TV devices. Compare that to the cable operators. The biggest of them, Comcast, has no more than 22 million subscribers. All the pay TV operators combined have about 95 million subscribers.”

The beginning of the end for linear, scheduled TV will come when the Internet players have too many subscribers for the content rights holders to ignore, Lai says. When that happens—and it may happen more quickly than many people expect—the content owners will begin to break their exclusive content agreements with the pay TV carriers. Instead, they’ll begin streaming their shows on their own websites, on video services like Amazon and Netflix, and via apps on platforms like Roku and Apple TV.

IDC’s Ireland believes we may be moving into a period when people will have to choose between pay TV subscriptions and online video subscriptions. “You’ll have a lot of consumers deciding whether Orange is the New Black or House of Cardsoutweighs Game of Thrones or Breaking Bad,” Ireland says. “They will buy one or the other, but not both. They may decide the Netflix shows are more important, but then they might watch all of those shows and then go back to Comcast.”

Absent their traditional monopoly on premium TV content, cable and satellite companies won’t have much left to entice new subscribers or retain existing ones with. Content costs are high, and companies like Comcast and Time Warner Cable must pass those costs on to customers to earn a profit. When consumers can get much of the same content on the Web à la carte, the sound of cords being cut should begin to get very loud.

Right now, the old deals are still in place: Content owners are honoring their exclusivity agreements with pay TV operators. Sure, you can watch lots of HBO video on mobile devices using the HBO Go app, but not before showing proof that you’ve already paid your cable company for HBO service. However, content owners, led by sports leagues, are starting to flirt with models that dismantle the fortresses built by cable and broadcast TV companies.

Why online TV will destroy cable

The main reason online, on-demand TV will eventually overcome closed-network, scheduled TV is simple: People want to choose when they watch their favorite TV shows. They don’t want to be locked down by a rigid network schedule. Pivot to the Internet, which respects schedules about as much as it respects geographic borders.

Advertisers are motivated to support streaming content, too. Unlike broadcast and cable TV, streaming video is relatively easy to quantify. A service like Netflix, for example, can provide advertisers with precise numbers on audiences sizes and viewer demographics.

“For advertisers, IP may have a slight advantage because it’s easier to know what person the content is being delivered to,” says IDC’s Ireland. “Set-top boxes are communal devices, so advertisers can’t really know who is sitting around watching the program running through the set-top box.”

The lack of à la carte programming has long been the bane of pay TV subscribers everywhere. For a variety of reasons that we won’t get into here (read the cable association’s explanation), pay TV operators have always sold big bundles of channels to subscribers, while denying customers the opportunity to choose and pay for just the ones they want to watch. Sites like Netflix and Amazon have no channels to bundle. You pay a monthly subscription fee in exchange for the right to browse, search, and stream thousands of titles.

“People hate à la carte,” says media consultant Richard Dougherty of the Envisioneering Group. “Many people say that à la carte might change in 20 years or so, but it will change in the next two years. That’s because Netflix has changed everything.”

Streaming media companies should also benefit from the wild popularity of serial dramas. Indeed, the TV content we love the most just works better on streaming TV platforms. Think about it: The modern serial drama isn’t so much a TV show with a series of loosely connected episodes as it is a 13-hour movie broken into 13 hour-long segments. That model is perfect for binge viewing, and nothing facilitates binge viewing better than Netflix.

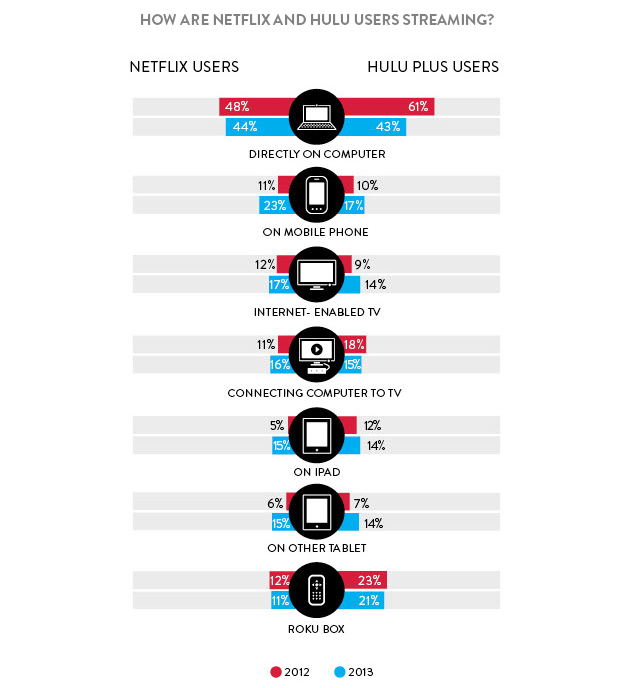

And people like to binge. According to a Nielsen report last month, 88 percent of Netflix members and 70 percent of Hulu Plus members say they’ve watched three or more episodes of the same TV show in one day. Viewers in the millennial generation are embracing streaming video like no other demographic, and they’re not necessarily glued to a 46-inch screen in the living room. Nielsen says the amount of time spent in front of TV sets by people in the 12-to-17 and 18-to-24 demos has consistently decreased since 2011. And since these demographics are prized by advertisers, Hollywood will be forced to deliver its content where viewers want to receive it.

The content owners call the tune

TV’s migration to the Internet is ultimately a matter of evolution, not revolution. There will be no explosions, no network chiefs diving out of windows onto Wilshire Boulevard. That’s because the TV content owners—networks like NBC and HBO, big studios like Sony TriStar, and cable network conglomerates like Viacom—hold the cards today, and they will still hold the cards when Internet TV becomes the norm.

They own the TV shows. Everything else is just distribution.

Content owners were terrified by the gutting of the music industry by Steve Jobs and the Internet during the 1990s and 2000s, and they will make sure the same thing doesn’t happen to video. Content owners will continue to nervously restrict the ways TV content can be distributed and consumed—until it makes financial sense not to.

Content owners and their exclusive distributors (cable, satellite, and telco TV) have carved out a big slice of our monthly paychecks for themselves—$86 a month on average, according to NPD Group, though NPD says the number could reach $200 per month by 2020 due to the rising cost of content (and that’s $200 just for video content, without broadband or phone service). Over the next decade, as TV distribution moves from traditional platforms to streaming platforms, content owners will make sure they get their usual share of that money.

If cable and satellite companies are forced out of the business of buying and distributing content, they’ll naturally fall back on the business of operating broadband networks. They are, after all, the de facto postal service for delivering streaming content, charging both senders (Netflix et al.) and receivers (consumers) to carry video streams into tablets, laptops, and living-room TVs.

It’s not a bad business to be in, says cable industry analyst Craig Moffett. “Being a dumb pipe would actually be a more attractive future for the cable operators than their current business,” he wrote in a recent note to investors. “Their competitive advantage is in distribution infrastructure, not in packaging and marketing.”

And here’s the tragicomic punchline: When TV shows flow into our households through a broadband pipe instead of through a cable, the service may come with a “suggestion engine” instead of a “programming guide,” and the brand names on the devices might be different. But we’ll almost certainly pay every bit as much for the content itself as we do today—if not more.

NIELSEN

NIELSEN

IMAGE: NIELSEN

IMAGE: NIELSEN