Hackers capitalize on other people’s mistakes. But they make their own as well.

Case in point: A massive breach of Adobe Systems’ network was discovered after the source code of numerous products, including the Web application development platform ColdFusion, sat parked on a hacker’s unprotected Web server open to the Internet.

The breach, which also encompassed 2.9 million encrypted customer credit card records, was announced by Adobe on Oct. 3. Adobe had already been investigating a breach when Alex Holden, chief information security officer of Hold Security, independently found what turned out to be the company’s source code on a hacking gang’s server.

Adobe’s source code “was hidden, but it was not cleverly hidden,” Holden said.

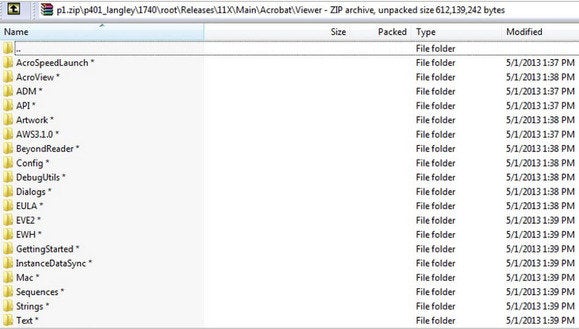

Perusing the directory of the server, Holden found a directory with the abbreviation “ad.” It was filled with “interesting” file names, Holden said, including encrypted .”rar” and “.zip” files.

It’s not clear if the files were stolen from Adobe in an encrypted format or if the hackers encrypted the files and then uploaded them to their server, Holden said. In either case, Adobe confirmed it was indeed source code.

Source code could make it easier for hackers to find vulnerabilities in Adobe’s products, Holden said. But so far, no new zero-day vulnerabilities—the term for a vulnerability that is already being exploited but doesn’t have a patch—have surfaced in the last couple of months since the source code was taken, Holden said. So far, the source code has not been publicly released.

In an Oct. 3 10-Q filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Adobe acknowledged the breach, but said it did “not believe that the attacks will have a material adverse impact on our business.”

But Adobe wrote later in the filing that its efforts to fight cyberattacks “may not be successful” and cause the loss of customers, incur potential liability and cost the company money.

The server had already attracted interest prior to the Adobe find. It was being used as a repository for stolen data by a gang that also broke into the networks of data aggregators LexisNexis, Dunn & Bradstreet and Kroll Background America, as reported by security analyst and journalist Brian Krebs.

The Russian-speaking gang—which doesn’t have a name yet—is still active. And there’s more to come.

The server also holds data stolen from several other companies, which have since been notified that they may have been struck by the gang as well, Holden said. Some of those breaches could become public if the companies elect to make an announcement.

Some states in the U.S. have data breach notification laws, but the requirements vary. In many cases, it may be up to companies whether they want to acknowledge a data breach depending on the severity and how one may affect their customers.

Analysts with Holden’s company specialize in gaining access to “deep web” or dark forums, used by cybercriminals to trade data and techniques anonymously. Hold Security offers a subscription service called ”Deep Web Monitoring” where companies can be notified if their data is found.

The secret forums are password protected and are often invitation only, so security researchers often pretend they’re one of the bad guys to get in.

Once inside, chatter from forum members can reveal what is hot, such as new vulnerabilities that can be used to breach networks. The forums try to filter out interlopers, but since no one uses real names, it can be hard to tell who is a fly on the wall gaining intelligence.