From bloggers to everyday users, almost everybody seems to have reacted to the release of the latest version of iWork with overwhelming negativity, and a general feeling that Apple is “dumbing down” its apps to appeal to a broader audience.

Judging from the amount of feedback that the new apps have received, the changes seem to affect just about everybody in some way; it’s probably fair to say, however, that power users will suffer the most from the disappearance of many of iWork’s more advanced features—a situation that, of late, seems to repeat itself every time Apple comes out with a significant update to one of its apps.

Strange days

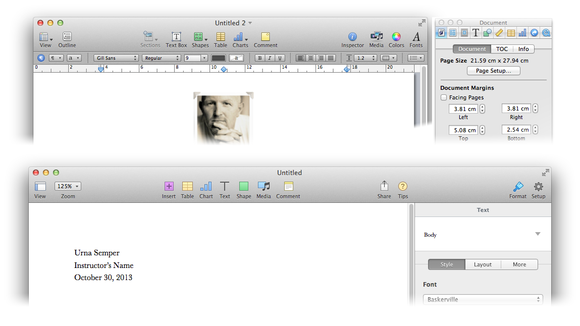

Most analysts seem to ascribe the changes that have befallen iWork to Apple wanting to bring feature parity to the various versions of its office suite. Because the suite has same capabilities across OS X, iOS, and the Web, users of Pages, Numbers, and Keynote can now share their files and collaborate in real time without fear that changes made on one device will be discarded on another due to a software incompatibility.

Undoubtedly, there is some truth to this, but I don’t think that it tells the whole story. Just about any piece of software Cupertino has released in the last few years, from operating systems to prosumer apps, has been driven by a deep-seated desire to simplify the way we do things. Office suites like Microsoft Office and (in a lesser way) iWork have always struck me as odd pieces of technology: overly complicated if all you want to do is write a letter, and woefully inadequate if you need to perform very complicated tasks. This makes them perfect targets for Apple engineers and designers looking to shake things up.

Then there’s the company’s current obsessive focus on unifying engineering and design resources across all its properties—something that Tim Cook keeps reminding us of at every opportunity, and something that I think is more important to Apple’s management than most analysts seem to believe. For all their limitations, the new versions of iWork look like they were built by the same company for the first time since…well, since there have been multiple versions of iWork.

Follow the white rabbit

I say this not necessarily to justify what Apple has done, but rather to figure out why. When you take away all the knee-jerk anger, much of the negative reaction to the release of iWork has been prompted by features that have gone missing and functionality that has been sacrificed seemingly only so that less-sophisticated users would be able to use the office suite. It’s almost as if Apple had gone off the deep end and decided to torpedo its own user-base.

It is possible, of course, that the world’s most valuable company is now run by a madman, but I have a hard time picturing Cook as an evil emperor who capriciously directs his management to make random changes while he cackles maniacally from atop a throne made of human skulls. A more realistic explanation for Apple’s actions is that it has identified a long-term goal and is, to borrow a favourite Jobsian expression, skating to where the puck will be.

In part, this goal is quite obvious: A set of simple (and free) office apps that anybody can use to edit and share documents across multiple devices and platforms plays well with Apple’s value proposition of selling top-notch hardware at a premium with the promise that cheap and plentiful software will follow. As a bonus, it strikes at the heart of Microsoft’s software-centric strategy, highlighting in sharp contrast the difference between the two companies’ respective ecosystems.

Ch-ch-changes

Along these lines, it’s also possible that Apple is “dumbing down” its apps because the company believes that the kind of comprehensive software to which we have become accustomed will no longer belong in the personal computing landscape of the future.

A traditional office suite like Microsoft Office made sense when it could be used in lieu of specialized software that would have been prohibitively expensive for individual users or small businesses, such as professional typesetting apps or enterprise accounting packages.

Today, however, many free or low-cost alternatives offer the same level of advanced functionality and better quality. For example, iBooks Author can be used to complement Pages or Word as a fairly comprehensive layout and typesetting tool that can produce all sorts of different outputs; if you need more, Adobe’s Creative Cloud gives you access to the company’s entire suite of design apps, which used to cost several thousand dollars, for a modest subscription fee.

In more general terms, the downward pressure on software prices is making complex apps that cater to power users less appealing both to developers, who have a hard time justifying charging premium prices to satisfy the needs of a relatively small subset of their customer base, and to consumers, who prefer apps that are more specialized, easier to use, and less expensive.

Looking down a very steep road

This is not, in itself, a bad thing. In the long run, we may well end up with apps that can focus in greater depth on the specific functionality that matters to a highly targeted user segment. Personally, I much prefer to use a really good word processor instead of a catchall app that also tries to be a typesetting tool, a mail merge app, a report generator, and who knows what else—particularly if I can buy, for a relatively small fee, whichever of those apps I need.

Of course, if you’ve spent the last several years setting up complex workflows that rely on features that have disappeared from iWork, no amount of analysis and speculation is going to mitigate the frustration of seeing your productivity being summarily tossed out the window in the name of progress. This, however, is a lesson that Apple learned the hard way with the release of Final Cut Pro X and the ensuing backlash, and it’s probably the reason why installing the new iWork suite doesn’t automatically remove any previous version of its apps.

Ultimately, it seems to me that Apple’s goal is to make everyone more productive with better tools that rely less on improvised hacks and more on professionally developed software. Hopefully, this will eventually pan out, despite the company’s slightly ham-fisted approach to innovation that has been alienating so many of its existing power users.