While I was visiting the Microsoft campus a few weeks ago—in suburban Redmond, just across Lake Washington from my beloved Seattle—I kept thinking of the old Vulcan proverb: “Only Nixon can go to China.”

If Microsoft is China, then that makes me Nixon in this story, I realize.

Prelude to war

Just as Nixon was an old Cold Warrior, I’m a veteran of the Apple/Microsoft war. My first computer was an Apple II Plus, bought way back in 1980.

The enemy in those days was Radio Shack (!) with its junky and clunky TRS-80. It was cheap, a ton of people bought it, and it wasn’t as good as an Apple computer. (Sound familiar?)

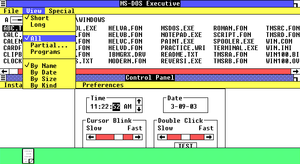

Then IBM came out with the PC, and IBM was the new enemy. Apple released the Mac, which we Apple faithful knew was unequivocally the better choice. And then came the march of the PC clones—and the enemy slowly shifted from IBM to Microsoft, which made the operating system that ran those clones.

What a terrible operating system that was. The user interface was particularly atrocious, not at all like our beautiful, elegant Macs.

But PCs were cheaper, and they out-sold Macs.

At first it was a complex enmity: Microsoft made Word and Excel, which were very good Mac apps. But it also made that ugly Windows, so, you know—boo.

Then Windows 95 came out—and Windows was darn near as good as Mac OS, and it became non-complicated, all-out war.

The fear

I was the last Mac user in the ’90s, just about, or so it felt like. If the word “bealeagured” didn’t exist, we’d have had to invent it, so that we’d have something sad—sad like sad trombones—to put next to Apple’s name.

The triumph of the enemy looked near, and that triumph would have meant that computers would be joyless and unlovable things.

That fear was deep and real. I used to debate with myself: Would I become a high school teacher or a waiter? Because I knew I’d have to quit the software business if Apple disappeared.

I could work my way up to restaurant manager. After a while I’d forget about the dreams I had before Microsoft took them away with its Windows-driven ascendance.

Do Microsoft employees love their children too?

We got so used to hating Microsoft that we didn’t notice when things changed. Some of us, didn’t, anyway. Or, well, I didn’t, at least.

Microsoft helped save Apple in 1997 by investing in the company and committing to future development of Microsoft Office for Mac, which was critical. Steve Jobs, freshly back at Apple, said, “We have to let go of the notion that for Apple to win, Microsoft needs to lose.”

I didn’t listen. I just noticed Bill Gates’s giant head on screen, which echoed that famous 1984 commercial). And I seethed.

But fast-forward to 2013, when I found myself on Microsoft’s campus recording some videos.

It’s just this software company, you know?

They will sing songs in the great halls about Apple’s turn-around. It’s one of the great achievements of our time.

And Microsoft—Microsoft is a company that makes hardware and software. Some is good, some is less-than-good. Like Apple.

Most importantly, Windows is no longer a threat to the computers we love. Not the teeniest, tiniest bit.

The Internet, standard file formats, and smartphones changed all this.

It used to be that you could live in an all-Microsoft world—and this was staggeringly common in the corporate world. You’d use Windows, Office, Internet Explorer, Exchange, and Sharepoint, and your in-house developers would use SQL Server and Visual Studio. All Microsoft all the time.

But you don’t need Internet Explorer to waste time on Facebook or YouTube. You don’t need Windows to watch animated GIFs or a Zune to play MP3s. You don’t need Sharepoint to share files.

Most recently, IT departments started adopting a Bring Your Own Device policy for smartphones. Those smartphones are rarely Microsoft smartphones—they’re iOS and Android devices. And this means that services that would have been Microsoft-only are now designed to run on everything.

The threat to Macintosh was not that Windows machines were cheaper, or that people had bad taste—the biggest reason was that they worked with everything. That was why Apple asked Microsoft in 1997 to continue developing Office for Macs, so we could at least say you could run Word and Excel on Macs.

But, these days, everything works with everything. (Well, except for Flash, but who cares.)

Give Microsoft a chance

But I’ll go further: There are reasons to like Microsoft:

Just about every geek I know—no matter how die-hard a Mac user they are—has an Xbox.

The company is no longer a copy machine. I expected their new user interface would be a lame copy of iOS. But it’s not. If anything, Apple’s designs will steer toward Microsoft’s flatter aesthetic.

They have a great history of excellent developer relations. (Unless you’re Netscape.) We can laugh at Steve Ballmer—but he was willing to get weird on stage for the sake of developers. Respect.

And Microsoft is learning how to fit into that diverse ecosystem that ended their monopolistic grip of the computing world. That’s where I’m most proud of them.

When I went to China

I have an example of the last two points. I’m a developer, and it’s developer stuff, but you’ll get the gist even if you’re a normal person instead.

One of the guys who works on Windows Azure Mobile Services gave me a demo of its support for iOS.

What? Microsoft supporting iOS? What? That isn’t the Microsoft (I thought) I knew.

Once I got over the shock, I expected that I’d have to write code in C# (a Microsoft language), that services would run behind IIS (a Microsoft webserver), and that I’d have to use Visual Studio (a Microsoft developer tool) on Windows, which I don’t have. That would be typical Microsoft, right?

Instead: The code is JavaScript, the webserver is Node.js, and I can write code in any text editor. No Microsoft things. The company even released some related code as open source and put it on GitHub.

(Microsoft? Hello, are you feeling okay?)

In other words, Microsoft noticed the world outside Redmond, and it likes it.

And I like them for liking it. And it doesn’t even hurt.

We’ve always been at war with Eastasia

If Microsoft isn’t the enemy—if it’s not a threat to our beautifully-designed way of life—then who is?

It would be easy to argue that Google is Apple’s new enemy, because of Android, or that Samsung is, because it’s behind the biggest threats to the iPhone and iPad.

But neither of those companies are threats to Apple. Apple is too big and successful to be threatened by any outside company, at least for the foreseeable future.

Instead, Apple’s enemy is Apple itself. It must attract and retain talent. It needs to get strong where it’s weak—particularly with syncing and online services.

It needs to retain that awesome balance between cautious incremental updates and the occasional, mind-blowing new.

It’s not easy. But nobody does it better than Apple.